How can we help a remnant of urban forest to regenerate its physical well being and form healthier relationships with people and its wider environment?

The regenerating future of Kohimarama Forest in Auckland’s Eastern Bays needs to be taken up.

Kohimarama Forest is a remnant forest that has become disconnected from its cultural history and wider ecological landscape. It has, however, never been cleared for pasture. As a result, the forest retains the memory of what the environment used to be; a mature ecosystem with complex relationships that do not exist in younger forests.

We are seeking to understand this ancient fragment of Aotearoa so that it can regenerate its ecosystem into one that is fully integrated into the environmental, social and cultural past and future of Tāmaki Makaurau.

If we can understand how to support Kohi forest in its process of regeneration, our learnings can be transferred to other communities seeking to support urban ngahere, so that they too, can have a better future.

We have an opportunity today, to rebuild relationships not only between people and their environment, but also between peoples.

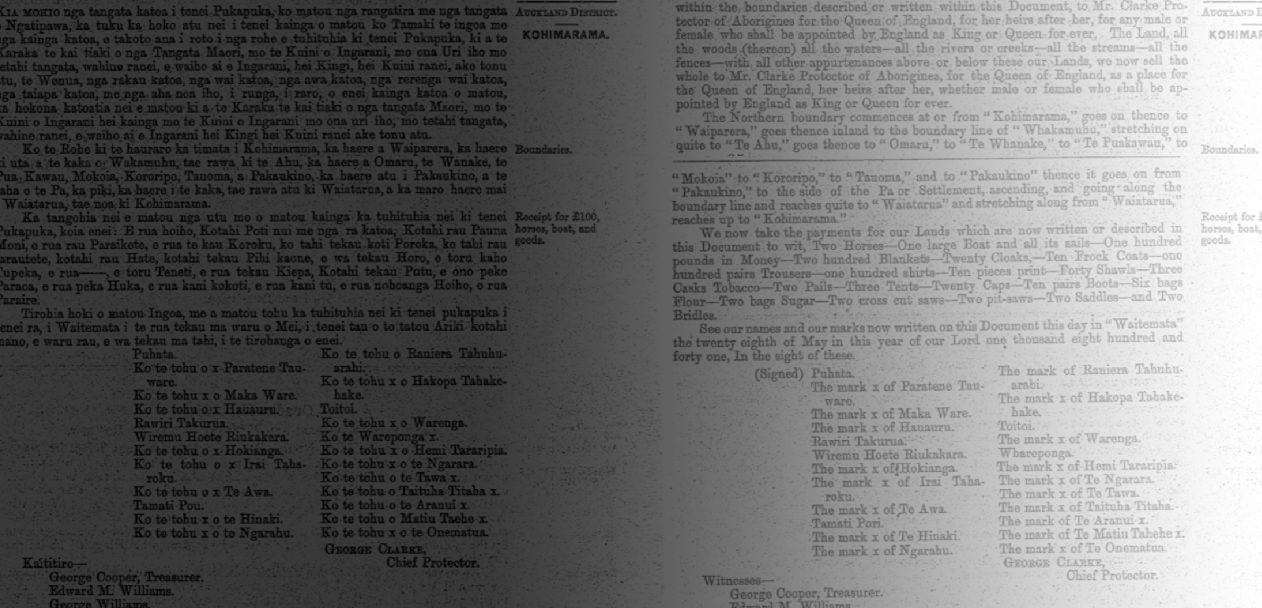

The Kohimarama block was sold by Ngāti Pāoa in 1841, to George Clarke, for the Queen of England. Clarke was an anglican missionary given the post of ‘Chief Protector of Aborigines’ to ensure Māori interests were met through the process of colonisation. Both Ngāti Whātua and Ngāti Pāoa gifted parcels of land soon after they signed the Treaty of Waitangi to solidify relationships with pakeha, to promote trade opportunities and to bring greater stability to Tāmaki Makaurau. Five years later, the ‘protectorate of aborigines’ post was disestablished by the crown and Ngāti Pāoa no longer had access to the trading post in central Auckland that was promised to them as part of their trade.

Today is the first time since 1841 that the future of Kohimarama forest has been made available for renegotiation. This is an opportunity to help reconnect Ngāti Pāoa with their whenua and to rebuild relationships that were damaged in the past, but are crucial to being able to move forwards towards a better future.

For more background watch: Morehu Wilson Ngāti Pāoa

Kohimarama Forest is part of an ecological corridor that links the predator-free islands to the Waitakere Ranges, Hunua Ranges and Riverhead Forest.

Wildlife in urban environments are often constricted to small, fragmented habitats with limited opportunities for migration. This can lead to local extinction. Forests of the size and connectedness of Kohimarama Forest can ensure that birds, reptiles, insects and other flora & fauna can continue to migrate through well maintained urban ecosystems. Weed removal and trapping by community groups have been a priority in the forest to reduce the spread of invasive species (ginger, jasmine and privet) spread by pests, but also to increase the chance that seeds of native trees are spread by birds travelling along the corridor.

Kohimarama Forest and the stream and wetland it protects is home to native flora and fauna — all of which are under threat.

The mature trees in Kohimarama Forest are more than 200 years old. A single tree can support more than 30 other plant species and increases the biodiversity in the forest by providing foraging and nesting opportunities. The forest is currently the home of native Tui, Pīwakawaka (Fantail), Ruru, nesting Kererū, and more recently there have been sightings of Kaka. Forests regenerate slowly and their full range of diversity (lichens, mosses, mycorrhizae, fungi and insects) are not easily replaced. The forest also protects the headwater of the stream that flows into the forest’s wetland area, and out to Kohimarama Beach. The stream is home to several native aquatic species including banded kōkopu, red finned bullies and eels. We now need to increase our understanding of these species to discover how we help the biodiversity of this forest to thrive.

After years of neglect under private ownership, the community is now helping the forest and wetland area to return to their former glory.

Kohimarama Forest is currently under private ownership. The steepness of the land and inaccessibility of the forested area has made maintenance difficult without crossing boundaries. 2 years ago the forest was described by a visiting ecologist as a "strangled jewel". Since then, in accordance with recommendations from ecologists and wildlife experts, locals have begun working together to rejuvenate the forest. Eastern Bays Songbird Project has been coordinating volunteers and receiving funding to help keep the land free from pests and weeds and increase the balance of native flora relative to exotic flora. As the urgent work necessary to avoid canopy collapse is reduced, indigenous knowledge needs to support scientific knowledge to ensure the forest is helped to regenerate into the future in accordance with its natural path.

The forest’s ability to absorb and retain water will be essential for Kohimarama as we brace for more severe storms as a result of Climate Change.

Kohimarama Forest is a valley area of over twenty-two thousand square meters that channels stormwater into a permanent stream that discharges at Kohimarama beach into the Hauraki Gulf. The wetland area beneath the forest canopy filters impurities from the surrounding suburban environment and, by absorbing or slowing runoff, reduces downstream flooding risks and improves the purity of water flowing into the ocean.

Any reduction in the surface permeability and water retention and filtering capacity provided by the forest will overload the pipes and open watercourses downstream, and detrimentally affect the quality of water being released into the Hauraki Gulf.

Proper planting along the stream edge is essential to the entire ecosystem from forest to sea and one of the most urgent things to address when starting any forest regeneration project.

We need to decide how its future can be managed so that it can achieve its full potential.

Under private ownership, the forest has been seen as divisible in parts. Maori have long understood that the value of urban ngahere can only be fully understood when forests are recognised for their relationships with the much larger ecosystem within which they play a part. Auckland Council is also recognising how connections between people and the environment are crucial to mental, social and cultural health. Forest rejuvenation Infrastructure and educational and cultural support is now necessary in order to help locally-led regeneration initiatives and provide opportunities for skills and resources to be shared with other restoring environments.

Links to school programs and volunteer groups provide opportunities for regeneration to be ongoing, as they develop knowledge and a sense of responsibility for the health of our environment in our future generations.

The forest has already become a reference ecosystem for other regeneration projects, providing seeds, plants and lichen to local nurseries.

Ecologists, botanists and lichenologists visiting Kohi Forest have revealed the extent of its ecological value. Firstly, as an example of an intact fragment of mature native forest, exhibiting an undisturbed native ecosystem, but also for its ability to provide a "cascade" of native seedlings that can be used to restore and invigorate other surrounding areas. Collaboration with Ngāti Whātua and Auckland Council has already led to this opportunity being utilised, with hundreds of kohekohe seeds and 'naturally uncommon' species of lichen being propagated from the forest.