Volunteering

Kaitiakitanga is based on the belief that there is a deep kinship between humans and the natural world.

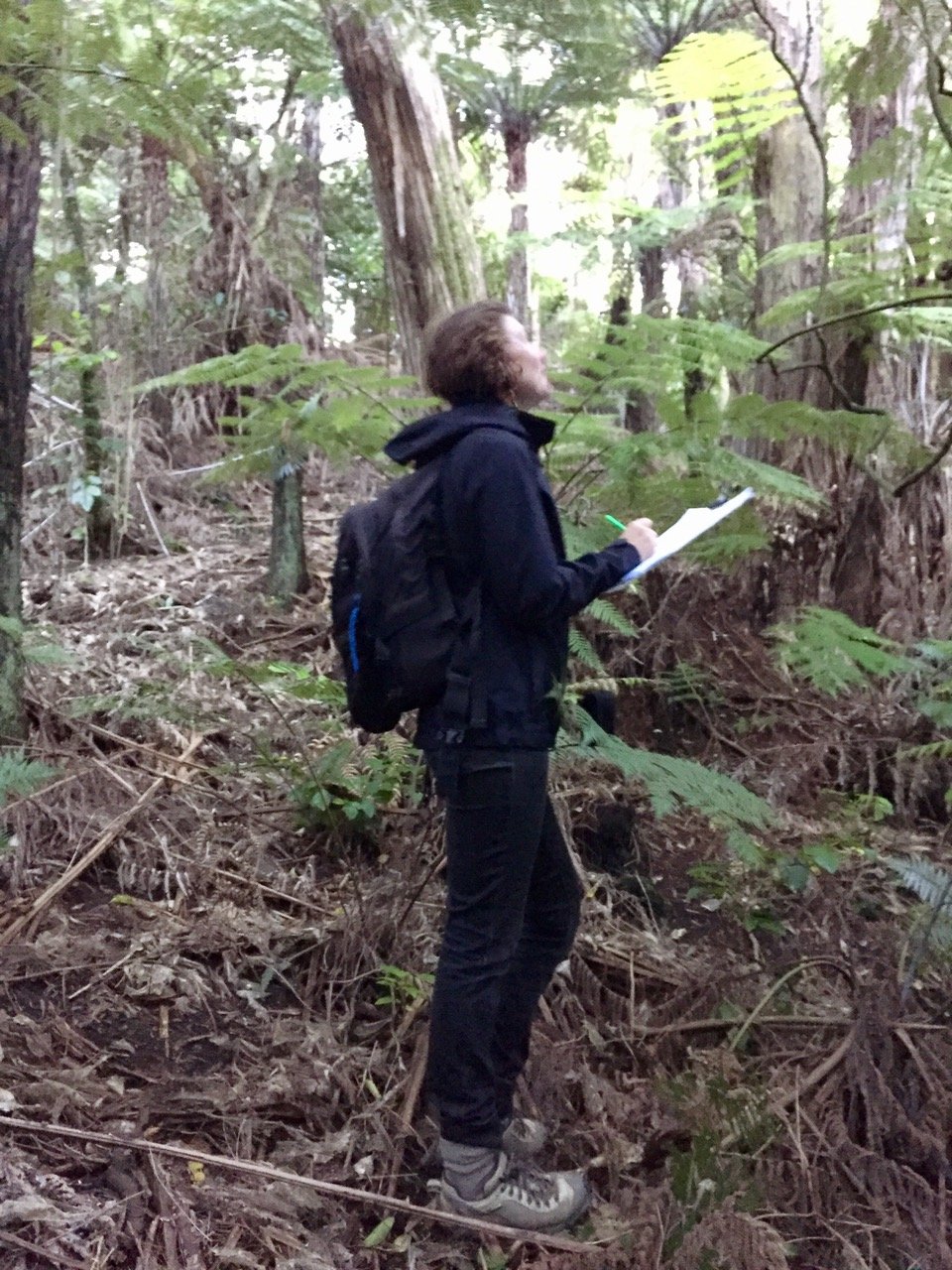

The state of Kohimarama forest has been a direct reflection of legal battles over rights of use and ownership of the forest that have taken place throughout its history. Today, something different has been happening. Eastern Bays Songbird Project is working together with local iwi and volunteers; weedbusters, trappers, botanists, ecologists, designers, and engineers, and is crossing legal and discipline boundaries to develop a better understanding of what is needed to bring the forest and people back into balance.

Tāmaki Makaurau

The Māori name for Auckland is Tāmaki Makaurau, ‘battle of a hundred lovers’. The name is a reflection of the region’s quality as an extremely fertile area of land and sea, desired by many and consequentially the site of much fighting. Ngāti Pāoa signed theTreaty of Waitangi in 1841 and they traded the ‘Kohimarama block’ including use of its forests and its waters soon after.

Māori believe that people belong to the land rather than that land belongs to people. Whanau (extended families) and hapu (sub tribes) would regularly establish different rights to the same piece of land. One group may have the right to catch birds in a clump of trees, another to fish in the water nearby, and yet another to grow crops on the surrounding land. Exclusive boundaries were rare, and rights to the use of land were constantly being renegotiated. There is no concept of land ownership in Maori language and it is believed that early trades can only have meant that tribes were offering to co-occupy the land in the hope of building a peaceful culture of agriculture and trade together.

Fish find their way from the ocean to lay their eggs in the stream in this forest, tui sing their song here, kereru collect and drop seeds here, and people are now weeding, planting and trapping in the forest to feel a sense of being a part of something bigger than themselves. Volunteering in this forest teaches every one of us that nature has no boundaries and that all species must play their part in keeping our home healthy both now and into the future.

Listening to the Voices of Trees

Volunteering in Kohimarama Forest on Wednesday mornings is a bit like using Roald Dahl’s ‘Sound Machine’. It helps you tune out of your everyday concerns and listen instead to the voices of the trees. Our purpose was, on this day, to release young native trees from the strangling mat of jasmine vines that criss-cross the forest floor and twist tightly round their still fragile stems. I imagined what the individual voices of the baby totara, mahoe and kawakawa trees might sound like, as they expressed their joy at being freed to stand up straight, and feel the warmth and light of the sun.

But when we were carrying out our check of the stream, (to clear blockages and notice the quantity of native fish life), we passed by the ancient kohekohe tree grove that is the jewel of this forest. We saw the beginnings of a tree house being built up in one of their branches. I did not only imagine the excited voices of children who had found a way to be amongst the leaves , I also began to wonder what a deep groan of pain might sound like, if it was emanating from a two hundred-year-old kohekohe, feeling a screw driven into its trunk. As an architect, I have often advised clients to remove or prune a tree in order to create spaces that capture better light or provide a perfect view. Today I was reminded to listen to the voices of the trees and all of the forest’s other creatures, who would tell me how their lives could be made better rather than worse through my designs, if I only had a ‘sound machine’ to hear them .

As we wound our way back out of the forest I very clearly heard the sound of tui and saw a kereru nesting in a tree. A piwakawaka followed along, chattering all the way. It seemed to be challenging our entire group of volunteers to take the message of respect for the forest with us, and to share it with anyone else we can.

Read Roald Dahl’s ‘The Sound Machine’ here : https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1949/09/17/the-sound-machine

Kawakawa tea for volunteers

The Maori creation story tells us that in the beginning the earth mother, Papatuānuku, and the sky father, Ranginui, were tightly embraced. Tāne Mahuta, the God of the Forest, was responsible for pushing his parents apart to allow light and life to grow between them. Kawakawa was sent to Papatuānuku, to mend her broken heart. The heart-shaped leaves of the kawakawa plant remind us of this story, and its medicinal capabilities have been shown to strengthen the heart’s capacity to pump blood around the body and to provide relief from pain; the perfect remedy for a broken heart.

There are guidelines for collecting the leaves of this precious plant. Begin by saying a karakia of thanks to Tāne Mahuta and Papaptuānuku, to acknowledge their gift. No more than three leaves must be harvested from any plant. Take east-facing leaves with the greatest number of holes, and never harvest when it is raining or at night. A sunny morning ensures the plants are at their healthiest, so the plant heals more quickly. The looper moth larvae eats only the sweetest leaves and activates the medicinal properties so the holes show us the best leaves to take. The gentle and natural tea that can be made from kawakawa leaves helps to detox the liver, kidney and lungs, cleanses the urinary system and relieves aching joints. The leaves also have anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties when mixed into a balm.

Tea : Pour boiling water into a teapot, add 2-3 fresh, lightly scrunched kawakawa leaves, and finely grated ginger. Leave for 3-5 mins. Add a slice of lemon and enjoy.

Balm: Scrunch a handful of leaves and soak in 500ml of olive oil for 5 days. Melt 100g beeswax in a little oil before adding kawakawa/oil. Cook for 4 hours at low temperature, stirring occasionally. Use muslin cloth to strain off leaves and pour into a clean jar. When cool, treat skin complaints like eczema, psoriasis, scrapes and burns.

LEARNINGS:

Give thanks to the forest and to the earth, notice the signs of the forest, listen to those who have come before you, and take no more than you need.

A fight to the death

A conversation I had with an ecologist came to mind today, as we worked high up at the edges of Kohi Forest, trying to release small karaka trees from jasmine vines that were climbing up their slender stems, in what seemed to be a fight to the death.

The ecologist highlighted the importance of a forest’s walls, not only for holding in moisture, but to provide a buffer zone for controlling what seeds are carried into the forest by birds and the wind. Many of the forest’s pest plants (like Jasmine ) were planted in urban gardens for their fragrance and elegance, but when their seeds are carried into the adjacent forest they become invasive if not regularly pruned. If neighbours of Kohimarama Forest and other urban ngahere can understand their role as ‘walls’ of the forest that ensure moisture retention and healthy buffer zones, then they might choose to plant native shrubs and trees, whose seeds are welcome in the forest, and promptly remove weeds that are not. The forest, the birds and the surrounding environment can then naturally grow healthier together.

For information on what to plant and what to remove click on links below.

What to remove: https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/environment/plants-animals/pests-weeds/Pages/caring-for-our-park-buffers.aspx

What to plant: https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/environment/plants-animals/plant-for-your-ecosystem/Pages/plant-to-support-native-wildlife.aspx

Do you have images you would like to share?

Submit them here: kohiforest@gmail.com